How Do We Think About What We Think About?: A long overdue examination

I don’t know about you, but lately I have experienced no shortage of issues vying for my attention. Most of them seem to be demanding that I claim a hill to stand on and emphatically plant my flag in the soil of the side I choose.

No do-overs. No take-backs.

I am called to decide once and for all.

If you are like me, the constant barrage of information (and misinformation) can leave me feeling like I’m in a game of tug of war.

And I’m the rope.

Perhaps you feel it too? There is so much riding on the decisions we make these days, that we would be remiss in failing to take a step back and examine how we are consuming information and what we are doing with it.

How we think about what we think is important. And perhaps more than at any other point in our lifetime, here and now is the time to really examine this. And consequently, the decisions we make that result from what we are thinking. The stakes are high. Too high to leave it to opinions and unexamined perspectives. Starting with our own.

The call is loud and clear. We must learn to respond well to a waiting and wanting world.

The weight of that has not been lost on me. It has caused me to take a deep look into how I think about the things I think about. So, I decided to share some of the challenges that have surfaced for me. Perhaps you will recognize them as challenges that surface for you too.

But before we dig into them along with some ideas on how we can develop our decision-making lenses, let’s make a commitment to ourselves and to each other. Let’s commit to getting comfortably uncomfortable. Then let’s be willing to get a bit more uncomfortable beyond that.

Let’s agree that we are going to do this together, and before we look for our differences, we will focus on the things we have in common, like our need to be seen; to be understood, known and loved. Because if we can do that, we can have the good, hard conversations we all need to have to grow and to make the best decisions possible.

With that commitment, let us suspend our alliance to “left or right” in favor of our alliance to humanity. And regardless of our affiliation, let us acknowledge that the left and right can either be two wings of the same bird, working together to help it soar. Or, the left and right can be two cheeks of the same a… well, you get the idea.

With all of that in mind, let us dig into some of the challenges that can arise as we think about how we think about things. And along the way, let us find some tools to help us do better. Because when we know better, we can do better.

· We think that emotion has no place in good decision making. So often, we focus so intently on the intellectual aspects of making decisions that we completely neglect the value of allowing our emotions to be part of the decision. We might be surprised to hear that this is a dire mistake.

It was just a few years ago when we began to really understand the importance of emotional intelligence over IQ in determining a person’s overall success and well-being in life.

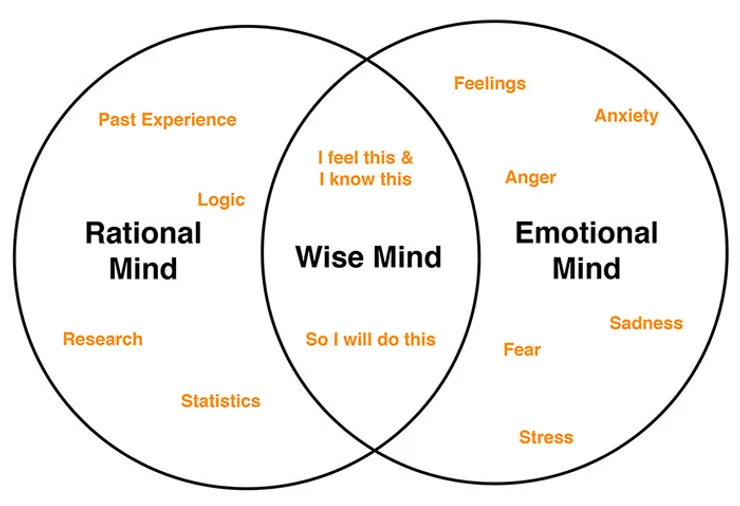

In therapy, we talk about finding our “Wise Mind” to help us make the best decisions. Guess what our “Wise Mind” is. Yep. It’s the place where logic and emotion meet. Bringing in an appropriate amount of emotion, combined with our logic mind creates the deep, wise mind we need to make the best decisions possible.

Without bringing our logic mind into the task, we forgo rationale and the importance of things like facts. But, without our emotion mind, we forgo equally important things like compassion and grace. Even justice and discernment require some degree of emotional investment. For the best decisions, we need the two working in tandem.

We have lost our ability to disagree from a place of grace and mercy. We confuse disagreeing with someone verses disapproving of someone. We somehow think that if a person feels a certain way and we validate that, we are somehow invalidating our own perspective. What we fail to recognize in these moments is that our emphatic need to be right is less about “being right” and often more about protecting our comfort. Not in a malicious way. Rather, in a way that says, “if I challenge this belief, it may require change and that is scary.”

· We listen to respond rather than listening to understand. We are so busy thinking about the thing we want to say that will convince the other person to leave their strongly held convictions in favor of ours, that we miss really understanding where the other person is coming from. We fail to see that behind the belief there is a believer; behind every question a questioner. And behind every reaction, a story that created it. Rarely are our beliefs created in a vacuum. Typically, they come from a highly personal place and the more rooted in our story they are, the harder it is to change those beliefs. (By the way, that goes for us as much as it does that “other person” we don’t agree with.)

When we fail to listen, it is inevitable that the other person will fail to feel heard. And when that happens, defenses elevate, and personal attacks are more likely. The sad result is our relationships suffer beyond the current disagreement on the table.

· We confuse a voice with all voices. Just because we find someone on “the other side” of an issue who aligns more with our own ideas, that doesn’t mean that all the people on “the other side” should agree with that person (or us). When we share those posts, the person might look different than us, but we are still only sharing our perspective. We still need to listen to all differing voices if we want to figure out how to do this “humanity” thing well.

· We think we are thinking for ourselves, but that might not be the case. No one wants to be told how to think. But I would humbly submit that if we are only listening to one kind of media, following one type of person, reading one type of book that offers only one perspective and only hanging out with people whose lives and experiences are similar to our own, then we might be confined in our ability to think for ourselves as well as our ability to learn and grow. We forget that we are thinking through the lens of our experiences; our successes, and failures, our fears and discomforts; what makes us comfortable and what feels safe. Our lenses are often crafted by generations that came before us. If we are unable to examine and even challenge some of this, we are not truly free to think for ourselves.

· We choose being right over being effective. This one can be confusing, I know. You are probably thinking, “Gina, how can you be effective if you’re not right?” The problem lies in the assumption that there are only two choices and only one goal. Choosing to be effective over choosing to be right means we put relationships first. Rather than cling to our version of what’s right, we can embrace a willingness to see that our “rightness” may only be right for ourselves.

When it comes to people who think differently than us, perhaps we could take a posture of curiosity rather than correctness. Through curiosity about another person’s perspective, we can fan the flames of compassion and grace. (Remember, those are important elements in making decisions from our “wise mind”.) If I am curious about you, then I learn. I can help you feel heard and understood. Even if we ultimately still disagree. And that is true effectiveness.

· We think that because we think a certain way, we should always think that way. This is another point that has deep roots. While it might seem benign, this one comes with some rather heavy implications. To examine this well, it might mean that we must examine why and how we came to think the way we do. For starters, this means asking ourselves what has our family of origin contributed to us thinking this way and is it truly helpful to the way we want to live? This is difficult! Because should we discover that it isn’t helpful, then we’re forced to look at what else we might need to reexamine in our beliefs and behaviors and that can feel overwhelming. Not to mention the relational dynamics that can be challenged by going against “the way the family thinks”.

· We fear change. Plain and simple. Whether it is something small like the route we take to work or as complex as the way we view people who are different from us, we fear the life-altering that must inevitably come with making change. But like we said before, just because we have always done something a certain way, doesn’t mean we should continue to do it that way. When we know better, we can do better. Sometimes the biggest challenge we face is to become willing to know better.

· (As believers in God) We interpret Scripture exclusively through individualistic, western and/or political lenses. We can’t omit the fact that in addition to bringing our logic and emotion mind into the decision making equation, as followers of Christ, our ultimate litmus test is WDJD (what did Jesus do? Because what would He do still leaves too much room for our subjectivity which is undoubtedly based on our own experiences and personal biases). Jesus was neither a "westerner" nor a politician. He held no allegiance to the left or right, nor to any particular group, class or race. What's more, while each person is individually important to God, His message most often was one that steered us toward a good that was for the common good; not just that of one person or group. (Although, the marginalized and broken do seem to be His favorites.)

We cannot leave out the examples and instructions Jesus gave us through His words and actions. Further, we forget the climate and condition of the original audience Jesus was dealing with and consequently, often miss the richness and nuances of what He is trying to teach us even today. Particularly as it relates to our differences in how we treat people who are not like us and our responsibility to one another.

OK! So, how are you doing?

If you are anything like me, reading through up to this point may have caused some cringe-worthy moments. Perhaps other points felt more like a punch in the throat. We know the points are hitting close to home the moment we enter into rationalizing our behaviors and approaches to decision making, and/or when our defensiveness gets turned up to eleven and we want to argue with all the reasons why a certain “challenge to examine” doesn’t fit for us (see virtually all bullet points ).

And I get that. I really do (again, see bullet points above).

But, if we are really honest with ourselves, we will find some of these points are speaking directly to us, beckoning us to examine our hearts and minds. Encouraging us to make changes in ourselves that help us make changes in our world.

Perhaps in reading this you have thought of a few more things that can help us examine how we think about the things we think about. If that is the case, please share! We are all in this together and learning from each other is a gift.

I promise to continue to share what I am learning about how I think. And I promise to have grace for myself and for others as we will all undoubtedly get it wrong from time to time. But if you make room for my humanness, I will make room for yours.

So, how about you? What do you think?